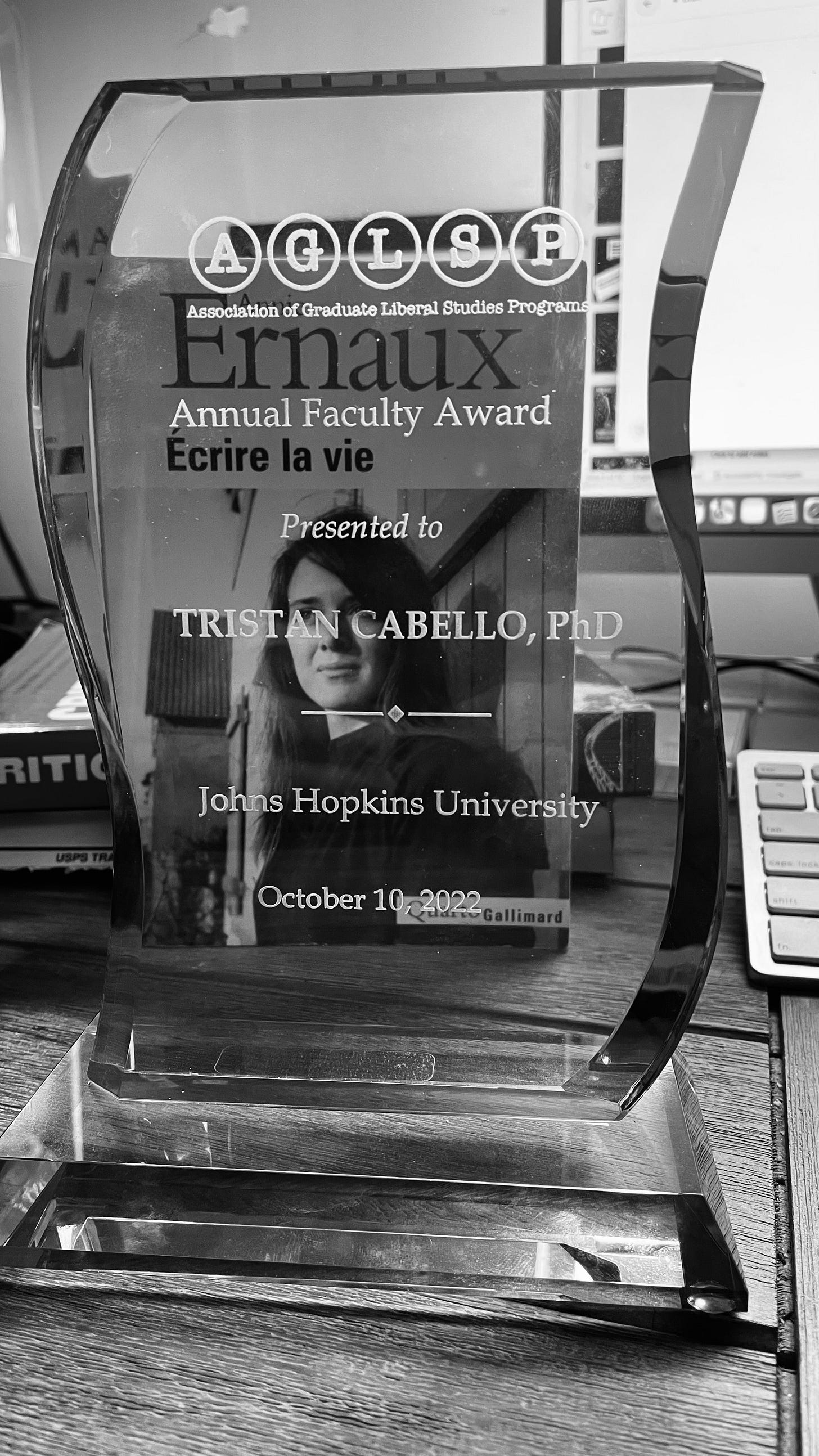

On October 11th, 2022, I received the Best Faculty Award from the Association for Graduate Liberal Arts Studies Programs (AGLSP) and had the honor of delivering a speech at the annual conference in San Antonio, TX. I am grateful for the support of the MLA Program Director Dr. Laura DeSisto, MLA Alumni Bryon Garner, and MLA Alumna Meredith Busch, who wrote letters of recommendation for this award. You can find the published transcript of the speech in Confluence, the AGLSP journal. An enhanced version is also available for you to read here.

Accomplishments are always collective adventures. This prize is therefore for the entire MLA program at Hopkins. This past year, I was able to provide my best in advising, teaching, and research because I received tremendous support from the Hopkins MLA family: our Program Director, our remarkable group of professors and our exceptional students. Thank you all.

Radical: the adjective perfectly encapsulates the essence of the MLA program at Hopkins. This year, we are celebrating our 60th anniversary, marking a history of leading academic discourse in the Liberal Arts. As the nation's first interdisciplinary graduate program in 1962, it pioneered interdisciplinarity in a time when it was widely disregarded. The program grew increasingly politicized in the 1970s with early inclusion of gender and race studies. In the 1980s, it stood against neoliberalism by providing timely courses that dismantled its ideology. The study of pop culture was introduced in the 1990s when cultural studies became popular. In 2016, the MLA began offering dynamic and highly interactive online courses, setting a new standard. Today, Dr. Laura DeSisto and I strive to incorporate a broader spectrum of viewpoints and voices, decolonize the curriculum and incorporate a commitment to social justice in all our classes.

The Liberal Arts are a radical force, aiming to free lives, particularly those of the marginalized. Last week, Annie Ernaux won the Nobel Prize and reminded me of the reason I am here today. Her masterpiece, The Years, struck a deep chord within me when I first encountered it in college. I was an 18-year-old student who had just moved to the big city to attend college. I had grown up in poverty-stricken post-industrial Northeastern France, surrounded by communities of color and second-generation immigrants. My parents never completed high school, and we had no books or exposure to culture at home. Ernaux's narrative was a revelation. Her story of growing up in poverty, moving to a bigger city to attend college, and experiencing a disconnect from everyone around her, including her parents and herself, resonated deeply with me. She described her life ( my life) using concepts like power, privilege, inequality, and justice that were entirely new to me. Her writing was concise, comprehensive. It completely rewired my way of thinking.

The simplest sentences uttered by my mother during my adolescence suddenly gained new significance. "I never enjoyed school; it was never my thing" my mother would say. For Ernaux, these words carried more weight than just a description of her experience. They represented a larger system of power and exclusion. Like Annie's mother, my mother believed that leaving school at 16 was a choice. She failed to notice that in her social class and village, all the women followed the same path of dropping out of school, marrying a local man, having children in their early twenties, and working as cleaning ladies. She didn't realize that her decision was not a decision, but the result of social inequalities, determinism, and class segregation - the outcome of a web of injustices. Meanwhile, for the most privileged, attending college was a clear and easy choice.

When I was eighteen, Annie Ernaux introduced me to the world of Liberal Arts. Her works encompassed sociology, philosophy, anthropology, history, literature, and music, opening my eyes to the power of interdisciplinarity. Her books were a rich blend of fiction and non-fiction, weaving together autobiographical anecdotes with sociological essays, historical articles, and political pamphlets.

Ernaux's teachings made me recognize the value of the Liberal Arts and how they could be used to dismantle social norms and uplift marginalized voices. I learned that the Liberal Arts could be a tool for liberation, but also a means of cultural domination if not approached with care. Her words made me see that pursuing a career in the Liberal Arts was not about imposing one's ideas, but rather a radical way to challenge societal norms and champion diverse perspectives.

In this post-covid era, the importance of the Liberal Arts as a radical, interdisciplinary, and emancipatory means to comprehend the world has become evident. To communicate this message to students and institutions, I would like to suggest three different perspectives.

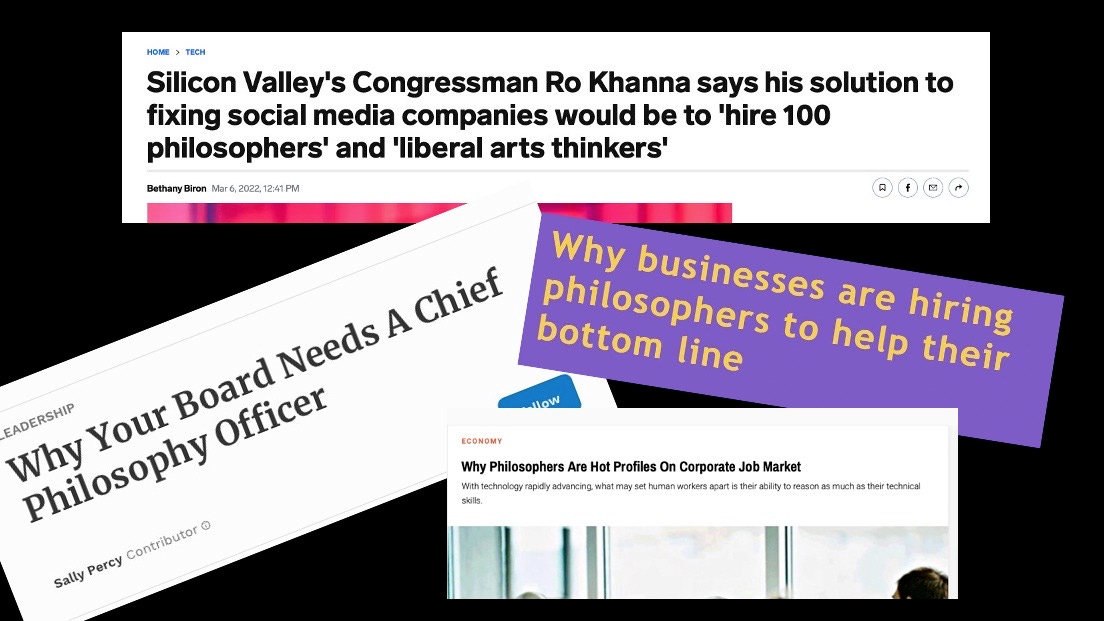

First, we need to explain the applied value of a Liberal Arts degree. In a world that is becoming increasingly complex and where we need to consume, work, travel, and eat less, the interdisciplinarity, diverse ways of knowing, and critical thinking that the Liberal Arts offer are more crucial than ever. The Covid-19 pandemic may have been a rehearsal for future pandemics that could be more devastating. As interdisciplinary thinkers who place the human condition at the center of their work, our students are best equipped to identify concrete solutions to these impending crises. Furthermore, most companies are now employing experts in work/life balance, social justice, DEI, philosophy, or history. Thus, we need to prepare our students for these positions.

We must highlight the transformative power of the Liberal Arts. Liberal Arts education is about more than just acquiring a set of skills or knowledge; it is about transforming students into critical, empathetic, and engaged citizens who can bring positive change to their communities. Our students are agents of change who challenge societal norms and work towards a more just and equitable world.

We should also emphasize the lifelong benefits of a Liberal Arts education. The skills and knowledge gained through a Liberal Arts degree are not only applicable in the workplace but also in all aspects of life: they never become outdated. By fostering critical thinking, communication skills, and creativity, a Liberal Arts education equips students with the tools they need to navigate an ever-changing world.

Secondly, we must discuss the Liberal Arts with the general public, outside of the Ivory Tower. In today's polarized society, where uncomfortable conversations have become increasingly challenging, our students are uniquely equipped to explain complex issues to the general public and establish connections between significant concerns of our time, such as social justice, climate change, and racial inequality.

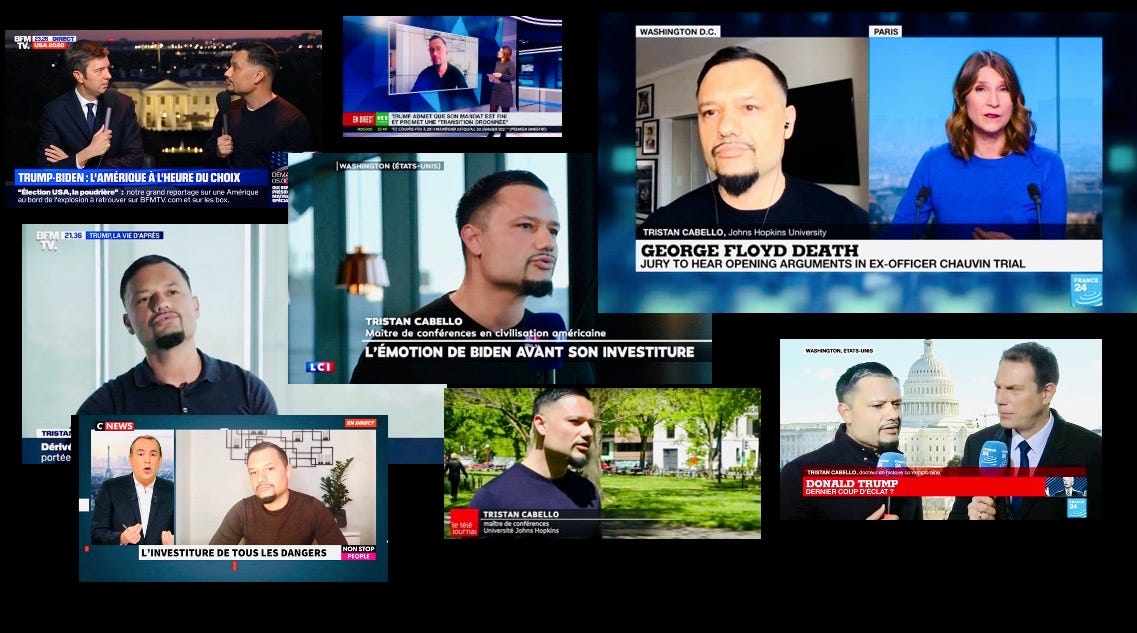

Allow me to share a personal story to illustrate this point. One of the first seminars I took as a graduate student was entitled “Becoming an Historian.” The last segment of the course was devoted to a discussion on "How to talk to the Media?" The recommendation (from our professor, a well-known and respected historian) was straightforward: journalists only wanted soundbites and engaging with them should be avoided at all cost. So, when I received a call from a French cable news network two years ago, inviting me to discuss Black Lives Matter and Critical Race Theory for an hour on election night, I initially declined, following the guidance I had received during my graduate training. But the journalist persisted, arguing that speaking to TV viewers was similar to speaking to students. Recalling my own experience growing up in a working-class environment where books were scarce, I recognized the power of television to expose me to new concepts, culture, politics, scholars, and writers.

With this in mind, I accepted the invitation and discussed Kimberly Crenshaw, James Baldwin, and Angela Davis on prime-time television the night Donald Trump was defeated. That evening, a young man from Aubervilliers sent me a message on Twitter, expressing his gratitude for hearing someone like me speak on television, and for helping him understanding intersectionality. This was a teaching moment, very similar to a classroom experience. This motivated me to appear more frequently in the media, but also to share my expertise with new audiences on social media platforms such as Twitter, Instagram, and even TikTok. The world is our classroom.

Today's generation of students are enthusiastic about public forums, and we need to support and encourage them in this regard. By engaging with the general public through various channels, we can communicate the value of the Liberal Arts beyond academic circles, and empower our students to apply their interdisciplinary knowledge and critical thinking skills to tackle the most pressing issues of our time.

Finally, we must diversify our programs, not just by attempting to diversify the curriculum, but by incorporating diverse voices into our teams and departments. Merely hiring faculty from diverse backgrounds is not sufficient. We must also work to retain and promote these faculty members, particularly those who have been personally impacted by the power of the Liberal Arts. A transgender person is better equipped to teach transgender studies, and someone who has experienced poverty firsthand can more effectively explain what it means to be low-income. Let’s make an effort to incorporate these voices and perspectives.

The truth is it remains challenging for individuals from lower socio-economic backgrounds to access graduate and doctoral studies in the Liberal Arts or become employed in Liberal Arts programs and departments. Therefore, we must engage in introspection and consider making dynamic shifts in our programs and departments. This may require individuals who have always dominated the narrative to take a step back in order to amplify new voices. Even if hiring capacity is limited, we can still share personal and relatable stories with our students to foster a more diverse and inclusive environment.

I have made a conscious effort to incorporate my personal experiences into my courses. I often share my own personal anecdotes to help my students connect with the material and understand the impact that scholars have had on my life, and can have on their lives. EP Thompson taught me about the history and dynamics of the working class; Pierre Bourdieu taught me about privilege and power; and George Chauncey taught me about what it meant to be a gay man.

I often take it further and share more personal experiences that have shaped me as a scholar and a person. Jean-Francois Lyotard taught me how to deconstruct the confusion I often experience, and Kimberly Crenshaw taught me how to deal with the anger I often feel. And… the best lessons about love I ever learned were from bell hooks.

A few semesters ago, I assigned her book, All About Love, in my Critical Theory course, and it deeply moved one of my students. She reached out to me to make a Zoom appointment to discuss the book, which had helped her process her feelings during a difficult divorce. What she didn't know was that I had also read the book during my own divorce, and I shared that with her. This led to a two-hour discussion about the intersection of sociology, culture, and history on the way we love.

In the end, the student explained: “Dr. Cabello, I have spent so much money on self-help books, life coaches, and therapy… who would have known all I needed was a Critical Theory course to answer my questions?”

And this, I think, perfectly encapsulates the radical power and future of the Liberal Arts, and their ability to transform individuals and society.

I wish you all a wonderful conference.

#AGLSP #BestFacultyAward #MLAprogram #HopkinsMLA #ConfluenceJournal #Interdisciplinarity #SocialJustice #MarginalizedVoices #AnnieErnaux #TheYears #NobelPrize #LiberalArts #AppliedValue #CriticalThinking #DEI #TransformativePower #Education #Radical